fellow jan schmidt

Originally, Frankfurt-based artist Jan Schmidt (born 1973), wanted to teach biology and chemistry. Although he abandoned this idea in favor of a career as a professional artist, he has retained a general interest in the sciences. This is important to understanding his works as they are fairly often reminiscent of tests and experiments.

Jan Schmidt often addresses the visualization of time in his works. Day-in day-out, he works stoically on recurring, occasionally meditative processes that remain recognizable. They are characterized by considerable craftmanship and a special appreciation for the respective material. In drawings, videos, objects and installations he devotes himself to individual issues that he evolves extremely carefully and meticulously. He combines this artistic approach with elements of chance that elude complete control and develop a life of their own within the work. These might be blocks of aluminum that he saws and whose fine shavings are assembled to form an installation, or an erratic limestone boulder from which he carves out fossils that date back ten million years.

As part of a travel scholarship from the Hessische Kulturstiftung in spring 2020 Jan Schmidt wanted to cross the Atlantic on a freighter and travel to Uruguay but his plans were disrupted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The artist had to break off his journey in Rio de Janeiro. In this interview he tells us how he dealt with this change to his plans, how he experienced life on the ship and how he produced art from drops of salt water.

Dr. Sylvia Metz conducted the interview.

Sylvia Metz Jan, how did everything begin? How and why did you become an artist?

Jan Schmidt As a youngster I enjoyed drawing. But I was never interested in art at school. I wasn’t a good pupil. But that didn’t stop me from considering becoming a teacher for biology and chemistry, two subjects that interested me. So, in 1993 I enrolled for a teacher training course at Darmstadt Technical University. During this time, I would meet up with friends in our rooms to do nude drawings. They were all people who later studied art or wanted to become set designers. I never really wanted to do anything like that as I said but after seven semesters I no longer enjoyed studying sciences. I applied to the Johannes Gutenberg-University in Mainz to study Visual Arts as a third teaching subject. Luckily, I got a place because I had already terminated my enrolment in Darmstadt. The first professor I would get to know was sculptor Ansgar Nierhoff – a very forceful personality. I liked his uncompromising matter, which sometimes verged on brute force. Suddenly, I had someone to bounce ideas off and I was grabbed by the desire to show him what I could achieve. I studied art to the exclusion of everything else and gave up my teaching training course entirely a few weeks later.

Metz That is a very brave course to take. Leaving behind the security of a teaching job in favor of free art. How did you continue with your art after taking this decision?

Schmidt After completing my studies in Mainz, I studied for three semesters at the Städelschule in Ayse Erkmen’s class.

Metz What made you go to the Städelschule?

Schmidt I really enjoyed studying in Mainz. The interaction was very intensive and usually revolved around the artistic work. There was little competitive thinking among students, but neither was there any public. The annual show was only attended by friends and family and that was a little different at the Städelschule. You can’t make art without feedback. When I’d finished at the Städel I stayed in Frankfurt, something I don’t regret. Since 2011 I have lived with my wife and our three children in a little old house in Frankfurt’s Bornheim district. I have a study there and everything takes place in a very small space.

Metz That sounds really idyllic. And given all that one wouldn’t necessarily imagine that you planned to cross the Atlantic on a freighter as part of your travel scholarship – that is more of a tough, uncomfortable undertaking. How did that come about?

Schmidt It is a must for everyone who meets the conditions that they apply for a scholarship from the Hessische Kulturstiftung. I had applied several times since 2002 but initially without success. The fact that it worked out in 2018 surely has to do with my family situation having changed. It meant a longer trip was not really feasible as our third child was born in 2018, and the other two were still young. I had suggested traveling by freighter to Montevideo. I had already been to Uruguay once before, had contacts there, and would have been able to work well there. I find the city fascinating and Buenos Aires is not far away. The two cities are located on either side of the mouth of Río de la Plata. But most of all I was looking forward to the time at sea.

Metz What interested you in particular about this project?

Schmidt Approaching the destination slowly. Gaining a sense of the distance that you would normally cover in a 12-hour flight. By boat it takes four to five weeks depending on the weather conditions and in the case of a freighter the waiting times prior to entering the ports. It is not as abstract as flying and your mind arrives at the same time as your body. One challenge was dealing with the limited possibilities and space on board. Not everything is possible on a freighter. On the one hand you are allowed to move about freely as a passenger, but on the other if 11 of the 12 decks are crammed full with cars and machinery and the twelfth is only one third of the boat’s length then you don’t have that much space …

Metz Yes, I can imagine that must be difficult. Were you in for other surprises on the journey?

Schmidt Yes, lots of things turned out differently to how they had been planned. For one thing I never actually arrived in Montevideo. The corona virus spread more quickly than our ship could cross the Atlantic. It was always there before us. When I set out on March 3, 2020 in Hamburg there had already been many deaths from the virus in Italy, but nobody could have predicted how things would turn out. Internet on board was very slow and only worked at certain times. I kept in touch with my wife via WhatsApp but I only really understood what was actually happening in Germany when I found out that the schools had to close on March 16 – when the ship was off Dakar and we were busy fishing. When you travel with a cargo ship you have to get used to waiting even in normal times, the procedures in the ports take longer or a crane breaks down and then you remain anchored for days. We waited off Dakar for a controller from the Senegalese health authorities who took the temperatures of the entire crew. The thermometer registered a body temperature of 26 degrees for me, in other words it was broken. But the controller was happy. At the time they had already started to close the restaurants in Uruguay as I found out from my contact there.

Metz I imagine it wasn’t easy continuing the trip under those circumstances, was it?

Schmidt It’s true that I began my 6-day Atlantic crossing with a queasy feeling in my stomach, but I remained on the ship to begin with. Then when I decided to break off the journey a few days later because the Latin American countries were closing their borders one after another things got really difficult: My Internet connection was too slow to book a flight. My wife in Germany took care of that but it was impossible to plan things any longer. On the one hand, we lay at anchor for days on end waiting to enter the ports in Brazil, or the other flights were canceled by the operators at short notice. It took a lot of persuasion and a large shot of good luck before I was finally allowed to leave the ship in Rio de Janeiro, and that only happened because I had a valid ticket to Germany on my smartphone. In short, I never reached my planned destination.

Metz What does not having achieved your original goal mean to you?

Schmidt Well, that’s something that happens all the time. It makes what does succeed all the more important.

Metz What did you take away from the journey, and what had the strongest impression on you during the journey?

Schmidt I had never before experienced being in a situation so completely beyond my control. After all, that is part and parcel of a journey by boat; you might get into a storm or something similar. But the pandemic is different, something the likes of which nobody had experienced before. We are still at the mercy of it today. I also had a lot of positive impressions: the vastness, the sky, the sea. The water never looks the same at any given time of the day. I observed the stars. At one point the Southern Cross appeared in the sky, that is only visible from the southern hemisphere. Nowhere else is the night so black as it is far out at sea. I crossed the equator and at twelve o’clock midday I stood on deck accompanied by a tiny shadow. I watched dolphins, and saw whales from a distance, swarms of flying fish, rays and sea turtles. I spent hours leaning over the railing and waiting to see what would come past. I also found it very impressive when we entered the port of Vitória in Brazil. The pilot came on board and we glided through narrow gorges with steep cliffs virtually within reach. It was also a good experience to fish with the crew, you get to know each other. Squid prepared the Philippine way was fantastic! Gerome, the sailor who accompanied me every day when I collected water samples, became someone I really valued talking to, and I learned a lot about life at sea from him. As I see it, not many positive things.

Metz I see, so you won’t become a sailor. If you could plan the trip again with the hindsight you have now would you do anything differently?

Schmidt I would take my family with me.

Metz What works did you produce during the trip and how is your project integrated into your work to date?

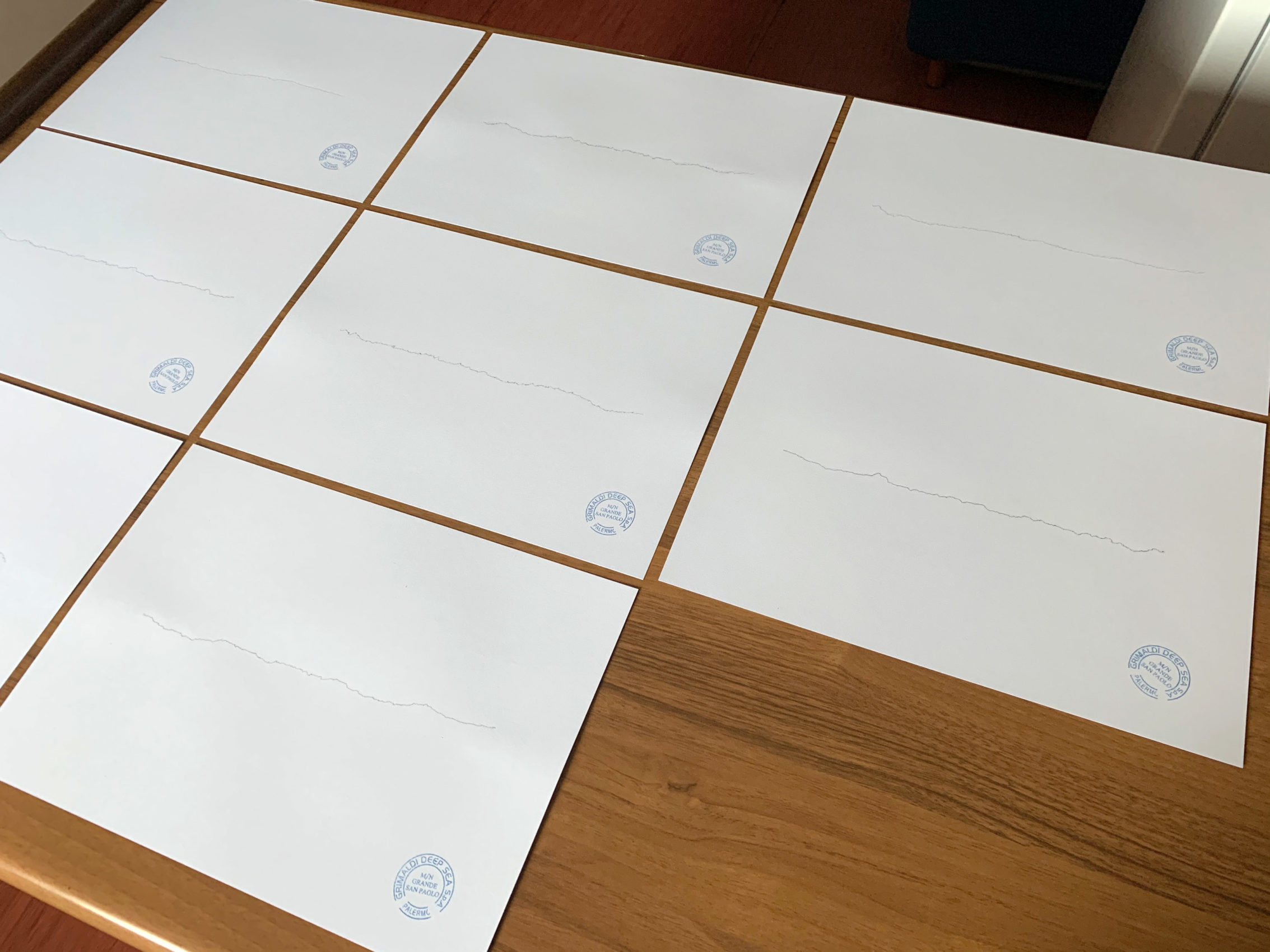

Schmidt I had given some thought as to what I could do on board, and had a whole suitcase full of material with me: marbles, a spirit level, ruler, chalk, pencils, binoculars, a microphone for my smartphone, a camera, printer ink, magnets, watercolor paper and so on. I wanted to record the movement of the ship, document the route we had covered, make sound recordings. And a lot of that worked out. For example, every day when the ship was moving, I drew water from the sea. Then I used a pipette to drip the water onto watercolor paper and let it dry. The result was small areas of salt and these fields together with a date, time and the exact GPS location of the place the water sample was taken constituted a kind of diary. This project had a lot to do with my 2018 Water Book: a sketchbook that I filled entirely with drops of water. After all, my work is mostly about processes that are somehow legible and visualize time processes. During my time on the ship, I also produced hand drawings, sound recordings and a video.

Metz What art projects are you now involved in as a result of your trip?

Schmidt I have just had two roughly six-minute soundtracks recorded on vinyl, the Neue Giessener Kunstverein has released the 7″ record as a limited edition. What you can hear are rhythmic ambient sounds in my cabin or the ship’s gym. Just a few days into my trip we got into a storm off the Bay of Biscay. The ship heaved violently in all directions; everything clattered and rattled. It was impossible to walk in a straight line. I used this rising, falling and tilting of the freighter as a “motor” for the marbles that move around themselves on the edges of two tin cans inserted one into the other. That can be watched in the Biskaya video.

I am currently evolving a form of presentation for the salt images; there will be a cooperation with Museum Wiesbaden as soon as the pandemic makes it possible. This preparation work for the presentation will be supported with a project scholarship from the State of Hessen, something I am delighted about. I also swept up soot from the ship’s deck (the engine runs permanently) and brought it back with me. It is black and oily. Perhaps I will use it later as a pigment. But these are just the tangible results of my journey. What is much more interesting is what I can’t put into specific words, things whose impact only becomes apparent much later.

Metz That’s right. Experiences like yours often still have an impact years down the line. Essentially, if you are lucky you can savor them an entire lifetime. What are you working on right now?

Schmidt At the moment I am working on an art-in-building project for the Mittelhessen University of Applied Sciences in Giessen. In the three-storey foyer of the new building for Mechanical Engineering and Energy Technology I am installing a nondescript box at the highest point. A random controller causes single maple tree seeds to drop from the box and they fall day and night in a slow spiraling motion to the floor. They remain there, are collected, swept away or disappear in other ways. The special thing about the seeds is that I will number them serially by hand: 2,400 a year, 48,000 in 20 years. Twenty years is the length of the contract I have with the State of Hessen. Every year I will fill the box with new seeds. As they are numbered the seeds can be placed in a temporal context. I hope with the artwork to create chance moments of happiness, triggered by a process that can normally only be observed outside in nature. Standing out against the white wall of the foyer that is over 13 meters high that is sure to be a special event. Perhaps someone will plant one of the seeds and get it to germinate. Naturally, that would be wonderful.

And currently I am working on a book with Andreas Bee about a project that I began before the trip and was able to complete in November 2020. The book is scheduled to be published in April.

Metz Interesting! What sort of work is it, can you tell us something about it?

Schmidt Sure. It is a project in public space that has altered steadily since January 2019, it has shrunk. Years ago, while out walking I discovered a large erratic limestone boulder that is not far from my studio. It was left standing beneath a bridge over the A 661 interstate following construction work. Originally, I had planned to hew a shape out of it. However, after just a short time I discovered small, fossilized snail shells in it whose perfect shape fascinated me. Later I worked on the boulder and carefully extracted exactly 509 of these shells from the stone, fossils roughly ten million years old. Already while I was removing the shells I began thinking about how I would present them and asked myself how I could relate the story of this chance find that led to my being occupied for some time. The first form of presentation is this book in which Andreas Bee and I asked ten authors to write down their thoughts on the project. These are wonderful texts some of which are very far removed from the actual work and as a whole produce a sizeable book rather than simply a documentation.

Metz That sounds really fascinating. I look forward to reading the book and to your upcoming projects! Thanks a lot for the interview, dear Jan.

Schmidt You are welcome. Thank you, Sylvia.

translation: Dr. Jeremy Gaines